What is new for Northwoods Drifter in 2026

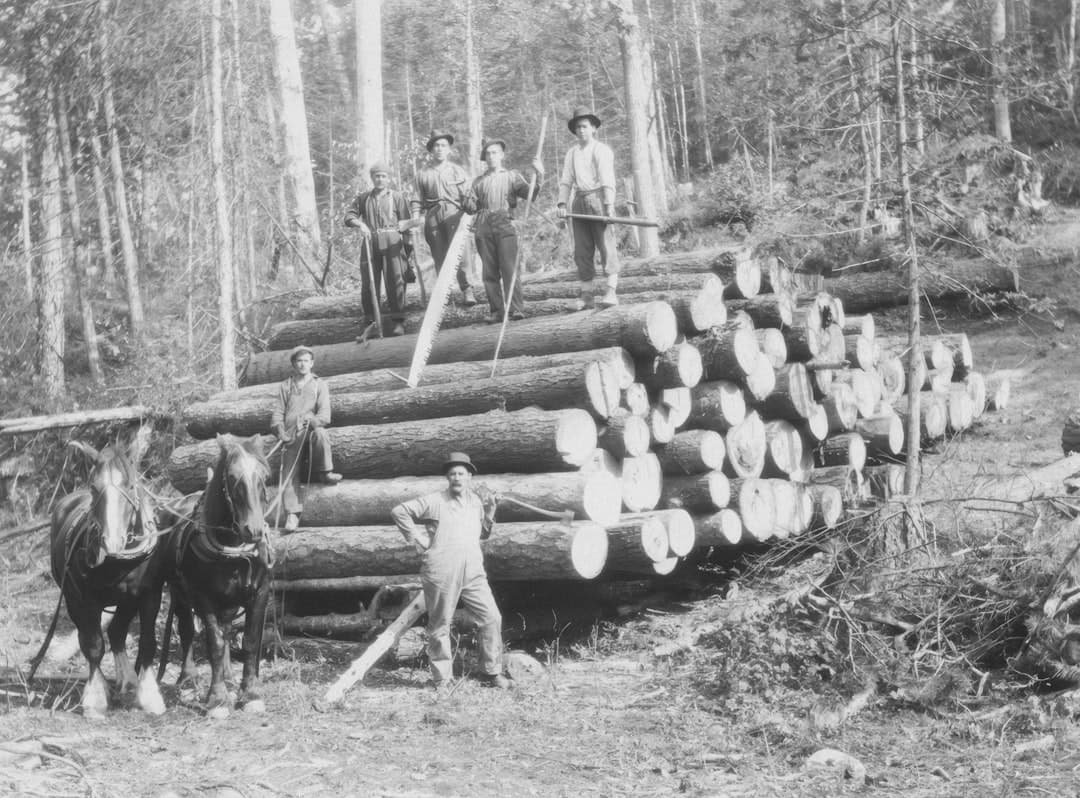

Drive through any Northwoods county and you’ll see the forests that define our region—millions of acres of pine, maple, and birch stretching to the horizon. But beneath that green canopy, an industry that’s sustained our communities for generations is struggling to survive. Wisconsin has lost roughly three million tons of wood consumption over the past decade, and the loggers who’ve built their lives around these forests are searching for a path forward.

The closures of pulp mills in Wisconsin Rapids and Park Falls left gaping holes in the timber market, with no immediate replacements to fill the void. For loggers across Vilas, Oneida, and Iron counties, this isn’t just an economic statistic—it’s a crisis that’s reshaping how they make a living and threatening the health of the forests we all cherish.

When pulp mills close their doors, the impact spreads like roots through the economic soil of the Northwoods. Henry Schienebeck, executive director of the Great Lakes Timber Professionals Association and a logger with three decades of experience, sees the full picture. “It’s not easy to get those markets back, so it’s been an adjustment,” he explains. “We just simply don’t have enough markets that impact loggers, truckers, land owners and a variety of different people.”

The numbers tell a stark story. Forest products jobs in Wisconsin plummeted from over 25,000 in 2001 to fewer than 7,000 by 2024—a staggering 46% decrease. The logging sector itself has been contracting at an average rate of 3.4% annually since 2020. Between 2014 and 2021 alone, the Northern region experienced a 20% harvest decrease, and that was before additional plant closures shuttered operations in towns like Goodman.

These aren’t just statistics on a spreadsheet. They represent families losing steady income, small towns watching their tax base erode, and county governments scrambling to compensate for lost timber revenue. Between 2022 and 2023, timber revenue for counties dropped 22%, forcing local governments to lean harder on property taxes or state aid—neither a sustainable long-term solution for rural communities already stretched thin.

Faced with dwindling markets, many Northwoods loggers have become masters of adaptation. The days of year-round logging operations are fading for all but the largest mechanized outfits. Instead, a new pattern has emerged: logging in winter when conditions are ideal, then pivoting to construction, excavation, or dirt work during the warmer months.

“They’re maybe just logging in the winter time and they might be doing some construction or dirt work or that type of thing, utilizing that same equipment in the summer time,” Schienebeck notes. It’s a practical solution that keeps equipment working and bills paid, but it’s a far cry from the full-time logging careers that once defined the Northwoods economy.

This shift reflects broader consolidation in the industry. Wisconsin had 20% fewer logging firms in 2010 than in 2003, and while remaining companies are hiring more workers, the overall trend points toward fewer, larger operations with expensive mechanized equipment. For the small, independent logger who loves working the woods, the margins are getting tighter every year.

Here’s something most folks don’t realize: healthy forests need active management. Trees don’t just grow perfectly on their own—they need thinning, selective harvesting, and regeneration work to maintain proper canopy health and prevent overcrowding. For decades, the logging industry provided this essential service while making a living.

“That’s a lot of forest management that’s not getting done right now because there’s no market for it,” Schienebeck warns. “Ultimately, it’s starting to impact forest health.” Without regular harvesting, forests can become overly dense, creating conditions ripe for disease, pest infestations, and catastrophic wildfires—none of which we want to see in the Northwoods.

Private landowners hold most of Wisconsin’s forestlands, but they can’t afford to maintain forests through thinning and regeneration work without the income that timber sales provide. County forests, state forests, and national forest systems lack the staff and funding to pick up the slack. The forest products industry isn’t just an economic engine—it’s been the primary mechanism for keeping our forests healthy and resilient.

Despite the challenges, there’s cautious optimism about emerging markets that could breathe new life into Northwoods logging. Sustainable aviation fuel made from wood fiber, wood-based insulation products, and cross-laminated timber for construction are all being researched and developed as potential game-changers for the industry.

These aren’t pipe dreams—they’re real products gaining traction in sustainability-focused markets. Cross-laminated timber, for example, is already being used in multi-story buildings as a renewable alternative to steel and concrete. Wood insulation offers superior environmental performance compared to synthetic alternatives. And sustainable aviation fuel could tap into the massive demand for carbon-neutral transportation options.

The catch? Patience. “A lot of them are being looked at,” Schienebeck acknowledges. “But no matter what we do it takes five to 10 years to actually develop that into a full-blown market.” That’s a long time to wait when you’re trying to keep your business afloat and your crew employed.

While waiting for new markets to develop, there’s another critical piece of the puzzle: ensuring there are skilled loggers ready to take advantage of opportunities when they arrive. The Wisconsin logging industry was already dealing with an aging workforce before recent market contractions, and the challenge has only intensified.

That’s where programs like Trees for Tomorrow in Eagle River come into play. By introducing kids to sustainable forestry and logging careers, these initiatives plant seeds for the future. Schienebeck, who was self-employed as a logger for 32 years, speaks with the passion of someone who truly loves the work. “They end up being really good jobs and once it kind of gets into your blood it doesn’t get out very easily,” he says. “There’s not a lot of days that go by that I don’t wish I was out in the woods.”

It’s that genuine love for the work—the independence, the outdoor lifestyle, the satisfaction of skillful timber management—that needs to be passed down. The Northwoods will always need loggers, whether for traditional timber products or the innovative markets emerging on the horizon. The question is whether we can keep the industry viable long enough to reach that future.

The Northwoods logging industry stands at a crossroads. The loss of three million tons of annual wood consumption isn’t something that gets replaced overnight, and the ripple effects touch every corner of our rural economy. Yet the forests remain, and with them, the potential for renewal—both ecological and economic.

The next few years will be telling. Will emerging wood products mature into viable markets fast enough to sustain logging operations? Can workforce development programs attract young people to a career that’s currently in flux? And will policymakers recognize that supporting the logging industry isn’t just about economics—it’s about maintaining the health of the forests that define the Northwoods character?

For now, loggers continue adapting, running smaller operations, diversifying their work, and holding onto the hope that the woods they love will once again provide a sustainable living. The Northwoods has weathered economic storms before, and there’s a resilient spirit up here that doesn’t quit easily. As Schienebeck’s words remind us, once logging gets in your blood, it doesn’t leave—and that stubborn passion just might carry the industry through to brighter days ahead.

Written by

Mike has been coming up or living in the Northwoods since his childhood. He is also an avid outdoorsman, writer and supper club aficionado.

News

NewsA bald eagle rescued near Minocqua highlights the lead poisoning crisis affecting nearly 90% of Northwoods eagles — and what local sportsmen can do to help.

News

NewsPark Falls honors Tom, Carol, and Stephanie Birchell through an ice fishing contest that celebrates community, raises funds for life-saving equipment, and keeps Northwoods winter traditions alive.

News

NewsBehind Eagle River’s legendary snowmobile trails are volunteer groomers like Dan Dumas, who transform rough, storm-battered snow into butter-smooth surfaces through skill, technique, and late-night dedication.

News

NewsNorthwoods bars and restaurants are celebrating early snowmobile season openings after two difficult winters, with businesses crediting volunteer trail clubs and hoping for sustained snow to support the region’s tourism-dependent economy.